“The real strain is the strain of waiting. Always waiting with the knowledge that waiting cannot end the war, and nothing stirring to take our minds away from petty worries. It makes us all grumpy and bad-tempered sometimes, and I know that I am often haunted by the same feeling that I always had in England, that the test is yet to come.” – to Estelle King, 20 May, 1916

“To be caught in youth by 1914”, J.R.R. Tolkien wrote later in life, “was no less hideous an experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years. By 1918, all but one of my close friends were dead.” One of those young men was a thoughtful, promising young artist named Robert Quilter Gilson (1893-1916), who had attended King Edward’s School, Birmingham along with Tolkien. Their small group of close friends called themselves the T.C.B.S. (Tea Club and Barrovian Society, named after the Barrow Stores at King Edward’s, where the group often met), believed that they were collectively destined for artistic and intellectual greatness, and left the school brimming with purpose and promise.

Gilson was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1912, a year behind fellow T.C.B.S.-ite Thomas Kenneth (“Tea Cake”) Barnsley, and read Classics. When the War broke out in 1914, he decided to finish his undergraduate degree and trained as an officer alongside his studies through the Cambridge University O.T.C. Upon graduating with a First Class degree in the Classics Tripos Part I, Gilson was commissioned as Second Lieutenant in the 11th Battalion Suffolk Regiment, known as the Cambridgeshires. The regiment deployed to France on 8 January, 1916.

At 7:30 AM on 1 July, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, Gilson led his men over the top near La Boisselle. The German guns, which were supposed to have been destroyed by a week of heavy bombardment by British artillery, were still working. When the Cambridgeshires advanced, the German gunners, shaken but still alive and alert, opened fire. A fellow soldier reported that Gilson walked calmly and steadily forward in front of his men, taking charge briefly after his commanding officers fell, until he himself was killed by a shell burst. On that first day of the Somme, Gilson was only one of 6,380 casualties from 34th Division, the division that sustained the heaviest casualties on the deadliest day of fighting in British Military history.

We have a window into Gilson’s brief life thanks to his prolific and eloquent letters to his school friends, family and his sweetheart, Estelle King, written from his time at Trinity College through to his last days on the Western front.

18 October, 1914

“Cambridge is such a definite idea and so different from anything else that I suppose I really expected to find the same Cambridge this term. It isn’t in the very least the same, and that meant disappointment.” – to his stepmother, Marianne Gilson, whom he called Donna, on 18 October, 1914

On returning to Cambridge for his final year of studies, Gilson noticed a distinct change in the atmosphere in Cambridge as a result of the War that was declared over the Long Vacation. “It is no more a unique place of high spirits and light-heartedness,” he writes, “but just about as pleasant a place as any other in these different days , and one’s friends are just as much one’s friends, even though they too are not the same.” He describes with satisfaction his new rooms in Great Court, which he got by earning a scholarship for the year, and Trinity in general: “I wish you could have seen it this afternoon with the low sun casting long shadows on the bowling green and making John’s a picture of contrasts in sun and shade and colour. And the border along the beautiful old wall is a splendid sight with chrysanthemums and Michaelmas daisies and scarlet salvias.” His love of Cambridge, and his love of descriptive writing, are evident throughout his letters written during his years at Trinity.

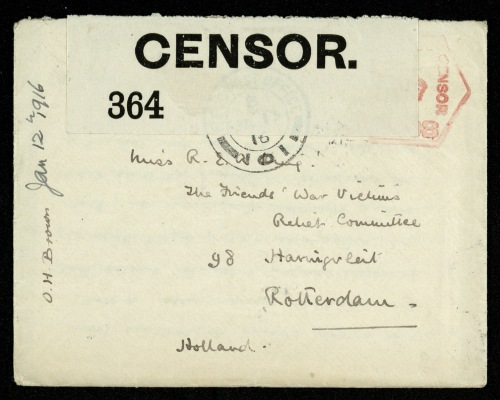

12 January, 1916

“It is very strange to look out from these windows across miles of flat peaceful country and say to oneself that only a few miles out of sight there are strange and terrible things going on that all Europe is watching. It is so unlike everything that one has ever thought of as real.” – to Estelle King on 12 January, 1916

With this letter is its envelope, with a sticker showing that it was opened by the censors. All letters had to pass the censors to ensure that soldiers were not giving away their movements, but Gilson ran afoul of the censors more than once, thanks to his lavish descriptions of people and places. Next to Gilson’s signature is the countersignature of O.H. Brown, a necessity that he resented, writing here, “I so much want to hear of your doings in Holland. Your letters will not be censored by anyone we know.” His ability to write is further hampered, he says on the previous page, by the fact that they have been allowed fewer candles on this night, so he is writing “in the midst of conversation”.

25 – 30 June, 1916

“I wish you could see a deserted garden that I passed the other day – all overgrown with long grass and weeds. It was a riot of bright colours. Larkspur and Canterbury bells and cornflowers and poppies of every shade and kind growing in a tangled mass. One of the few really lovely things that the devastation of war produces.” – to Estelle King on 25 June, 1916

“There are many grand and awe-inspiring sights. Guns firing at night are beautiful – if they were not so terrible. They have the grandeur of thunderstorms.” This letter describing a peaceful deserted garden was written amid the tumult of a week-long artillery barrage of the German front line. This was to be his last letter to Estelle, written from a tent some way from the trenches, where he had the luxury of “being able to walk about over stretches of grass” and re-reading some of her letters to try to conjure up in his mind where she was. “You have managed to give me a wonderfully clear picture of your Dutch surroundings, which is exactly what I want.” He did not sign off the letter and instead closed with, “It is so hateful being cooped up in the trenches – caught in a trap, as it sometimes seems. – Rob.”

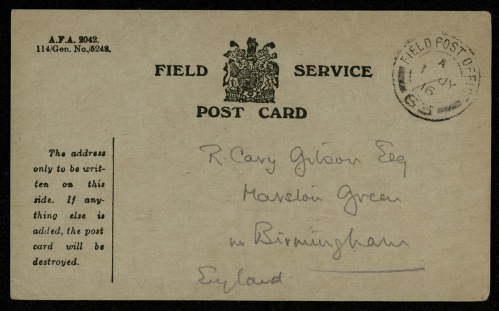

“I often think of the extraordinary walk that might be made all along the line between the two systems of trenches. That narrow strip of ‘No Man’s Land’ stretching from the alps to the sea is a most extraordinary phenomenon.” – to his father, Robert Cary Gilson on 25 June, 1916

On the same day, Gilson sent his father a long letter, in which he seems to have been in a reflective, philosophical mood, reflected in the quotation above. He apologised for sending fewer letters lately, and says, “I take your word that a postcard is sufficient to fill a gap when I cannot manage more”. After this letter, on 30 June, Gilson sent his father one final field postcard with statements deleted as appropriate:

“I am quite well. / I have received your parcel. / Letter follows at first opportunity.”

The next day, the Battle of the Somme began.

Many thanks to Julia Margretts and family for the kind loan of photographs and letters and for permission to reproduce them.

Further reading:

John Garth (2003) Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle Earth.

John Garth (2011) “Robert Quilter Gilson, T.C.B.S.: A Brief Life in Letters.” Tolkien Studies, 8(1).

See also our interactive timeline of World War I for a look at some of the events that shaped Trinity’s wartime experience.

Just to give the Trinity Library blogger some feedback. The posts on the First World War are absolutely excellent, and well-illustrated. I am enjoying them immensely.

Peter Elliott (1971)

7 Cantaloup

11290 Alairac

France

Tel: +33 4 68 72 52 30

Mob: +33 6 29 20 71 93

Thank you very much for your feedback! We are pleased to be able to share these stories with those who may not be able to visit the exhibition in person.

Pingback: Trinity and the First World War | Trinity College Library, Cambridge

Pingback: 1st July 1916 – Castle Bromwich and Marston Green | Solihull Life

Pingback: La King Edward's School produce un documental sobre Robert Q. Gilson | El Anillo Único

I live in marston green , and just visited the memorial ,,,, with his name on ,,,,, nice to know in his short life he achieved so much ….