This is the first of what we hope will become a series of guest blogs about material from the Library. Today’s post is by Dr William Kynan-Wilson, Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Aalborg University and Associate Scholar, The Skilliter Centre for Ottoman Studies, University of Cambridge

The late sixteenth century was a period of unprecedented contact between England and the Ottoman Empire. The initial stimulus to these early exchanges was trade: following the signing of a treaty between Queen Elizabeth I and Sultan Murad III in 1580 English travellers and merchants journeyed to the imperial capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) in ever increasing numbers. Alongside trade in lucrative commodities many Europeans developed a deep fascination with Turkish art and architecture, religious culture and societal organisation.

European taste for the Orient took many forms. One of the most popular of which was a book depicting customs and characters commonly known as an Ottoman costume album. These manuscripts adopted a simple, accessible, and flexible format: individual figures were depicted against a plain background and were identified via their clothing, props and often a brief descriptive label. Each album contained a diverse set of drawings including single-figure compositions of the sultan and his court, foreign merchants, and religious officials, as well as scenes of Turkish customs, such as women walking to the bath-house, an imperial wedding procession (see above), and vivid images of public execution. In this way the social, religious, and ethnic diversity of Ottoman society was neatly conveyed to a western audience that bought these books as travel souvenirs.

The Dryden Album (MS R.14.23) in the Wren Library at Trinity College is an early and important example of this genre. Both the artist and original owner are unknown, but the style and iconography allow this book to be attributed to a European artist and dated to circa 1580-90. The fifty-seven watercolours in this album are not of the finest artistic quality. Indeed, in 1901 M. R. James brusquely described the images as “all coloured, and rather rude.” The humble artistry does not diminish the importance of this book as a record of early European contact with the Ottoman world. Rather, it illustrates the emergence of a vibrant studio system through which European artists in Constantinople produced great numbers of these albums for foreign visitors. We rarely know how much these manuscripts originally cost, but it was evidently a lucrative market that Ottoman artists tapped into from the seventeenth century onwards.

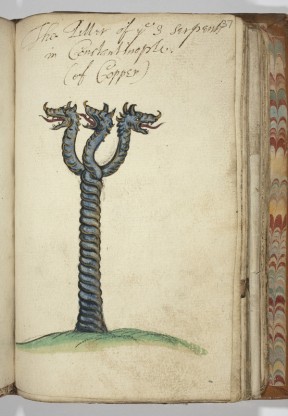

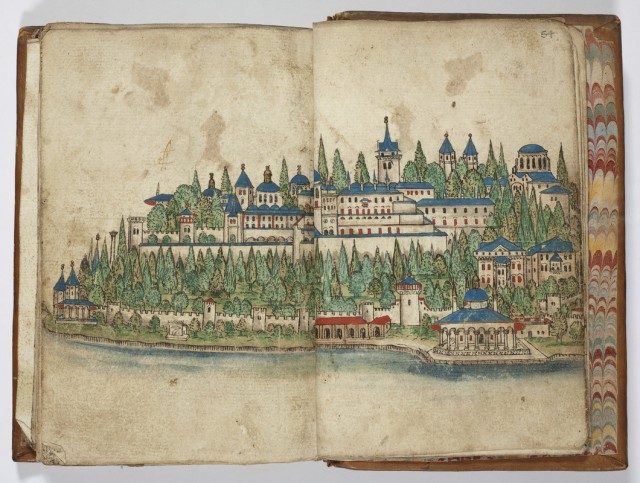

The most interesting element of this specific manuscript concerns the brief English labels that accompany most – but not all – of the drawings. In general, the glosses provide an accurate albeit terse overview of the city. One drawing depicts an ancient statue of a three-headed snake that still stands in the ancient Hippodrome. The English label reads: ‘The pillar of ye 3 serpents in Constantinople (of copper)’. Other monuments, such as the panoramic view of the imperial Topkapı Palace (see below), are tellingly unlabelled. The original owner may have been unfamiliar with the specific monuments depicted.

The labels attached to other drawings are even more revealing. For example, the drawing below depicts a man sporting a sheepskin cloak, a coloured skullcap and a gold-hooped earring. In his left-hand he holds a stick and in his right-hand he holds a small gold cup. The character is labelled: ‘A Coffee drinker’.

However, by comparing this image with examples found in other contemporary Ottoman costume books it is clear that this character is meant to be a wandering Islamic dervish. The red marks on his chest and arms are the result of the dervish cutting his own skin out of religious devotion.

Such dervishes were known for consuming coffee in order to fuel their spiritual exertions, and this may partially explain the appended label. More likely still, it is the prop of the golden cup (used for begging) and the deep association between Turkey and coffee that informed the reader’s response to this image. Another image in the album, which shows a water-seller with a golden cup, is also misidentified as a coffee drinker. Thus, certain characters were identified in very different ways by very different readers, and often on the basis of cultural associations and the iconography of the albums, as opposed to straightforward personal observation or even direct experience of life in the Ottoman world.

These seemingly simple albums performed many functions. On one level, they were souvenirs of travel that provided vivid and entertaining illustrations of Ottoman society. The bright, accessible and versatile format of these books ensured their popularity for more than three hundred years. Indeed, early photographic albums of Constantinople from the nineteenth century retained many of the iconographic and structural features of these earlier manuscripts. Above all, these albums played a crucial role in crafting wider European perceptions of the Ottoman world. They influenced how European travellers to Constantinople responded to and understood the city around them, and they also proved a powerful mode of experience the East vicariously. With these pages some of the colour and glamour of the Orient was translated into sixteenth-century England.

For further information see:

Kynan-Wilson, ‘Souvenirs and Stereotypes: An Introduction to Ottoman Costume Albums’, Heritage Turkey, Vol. 3 (2013), pp.35-6

Pingback: Trickle paper | Making Book

Pingback: 200th Blog Post – Trinity College Library, Cambridge